“If life was a million years long, sure, I could spend some of it people-pleasing… but because it’s so short, there’s no time to please.”

Alain de Botton

In a way, much of what we do is an unspoken bid for the goodwill of other people. Beneath our careful words and curated actions lies a tender hope: to be seen, acknowledged, and valued.

The pursuit is deeply human - a reflection of our need to connect and belong - but it carries in it a hidden vulnerability: the attention we long for is fragile, conditional, and most dangerously, beyond our control.

“The wise person will not spend their life pursuing popularity. It’s a will-o’-the-wisp. Far better to search within for one’s own values and goals.”1

A fair question to ask is: What does it cost us - emotionally and existentially - to tie our behavior to the fluctuating currency of approval? And another: What might we gain from greeting ourselves with the warmth we so desperately seek from others? The answer to both is the same: our freedom.

Freedom, in its truest form, isn’t about leisure or luxury. It’s about living in alignment with what feels right to us, even when our choices diverge from the expectations of the people we share life with. To be free is to risk the disapproval of others in order to build an honest existence.

Below are a few notes to help you recover inner clarity and bring your truer self back into view. I hope they remind you to value of your own voice and not be embarrassed by your wishes and ideas.

To Be Free

Thoughtful Diplomacy

The Separation of Tasks

Between Knowing & Doing

Afterword: Lessons from the Playroom

Thoughtful Diplomacy

The first thing to know about freedom is that it doesn’t require rudeness. It’s entirely possible to honor your preferences with kindness, sensitivity, and grace. In fact, good manners and independence are natural allies.

“Thank you so much for thinking of me, but tonight I wanted to practice my music…” “I appreciate the invitation, but I’ve set this evening aside for pottery and a podcast. I’d love to join another time…”

The truth may feel awkward (we’ll visit that next), but it doesn’t need to feel harsh. There’s no call for spectacle or alienation. Self-expression, at its best, isn’t about shutting people out - it’s about inviting them into a shared understanding, a sympathy built on respect for one another’s aspirations.

“A real conversation always contains an invitation. You are inviting another person to reveal herself or himself to you, to tell you who they are and what they want.”2

In this way, freedom becomes less about “setting boundaries” or “saying ‘no’” - and more about nurturing an atmosphere where individuality can be celebrated. By inspiring our closest companions to embrace this perspective, the weight of obligation can be lifted, and our lives can become richer and freer together.3

Graduation, John Baldessari 2017

The Separation of Tasks

Even with the best intentions, our early steps toward freedom can feel clumsy. Others might misinterpret our decisions as selfish or defiant, and that’s where clarity becomes essential.

In The Courage to Be Disliked, Ichiro Kishimi draws on Adlerian psychology to offer us a liberating concept: the separation of tasks. The principle is simple but powerful: Your task is to live in alignment with what feels right to you. How others react is their task - and crucially, not yours to control or carry.

“Being praised means that you’re receiving judgment from another person as ‘good.’ The measure of what is good or bad is the other person's yardstick. If receiving praise is what you’re after, you’ll have no choice but to adapt to that yardstick and put the brakes on your own freedom.”

When we’re overly worried about offending or being judged, it’s often because we’ve dissolved these distinctions - we haven’t separated the tasks yet. We’re still blurring what belongs to others with what belongs to us, and we take on responsibilities that aren’t ours.

The next time you feel tension between what you want and how others might react, take a moment to ask yourself, “Whose task is this?” Calmly sort out what’s yours from what isn’t, and then, with a quiet confidence, move forward.

Drawing & Prints, Barnett Newman 1944–1945

Between Knowing & Doing

Freedom may begin in the mind, but it needs to extend into our actions to become real. It’s one thing to understand the separation of tasks in theory; it’s another to live by its clarity.

This transition - between knowing and doing - is often where we stumble. We second-guess our instincts, wait for perfect conditions (like weekends or retirement), or fear that certain behaviors might damage our reputation. The slightest change in how we’re seen obsesses us, and so we trade appearances for opportunities, holding ourselves back to protect an image.

“Man is born free but lives in chains.”4

I know this hesitation well, and my strategy is asymmetric: big perspectives, small actions. I remind myself how immense and indifferent the world is (how its agenda is uncertain and highly abstract), and then I focus on small steps to strengthen my sense of personal freedom. Here are a few examples:

I dress for comfort, not display.

I read children’s books alongside best-sellers.

I take the scenic route, even when it’s less efficient.

I leave my phone behind for a few hours each day.

I willfully ignore much world news.

These acts are small but deliberate, and that’s the point. Cultivating freedom isn’t a dramatic flash or grand rebellion; it’s an evolving practice, built through steady, consistent choices rather than a single, defining leap. Over time, as our practice deepens, we gradually come home to ourselves, and the life we build begins to feel unmistakably our own.

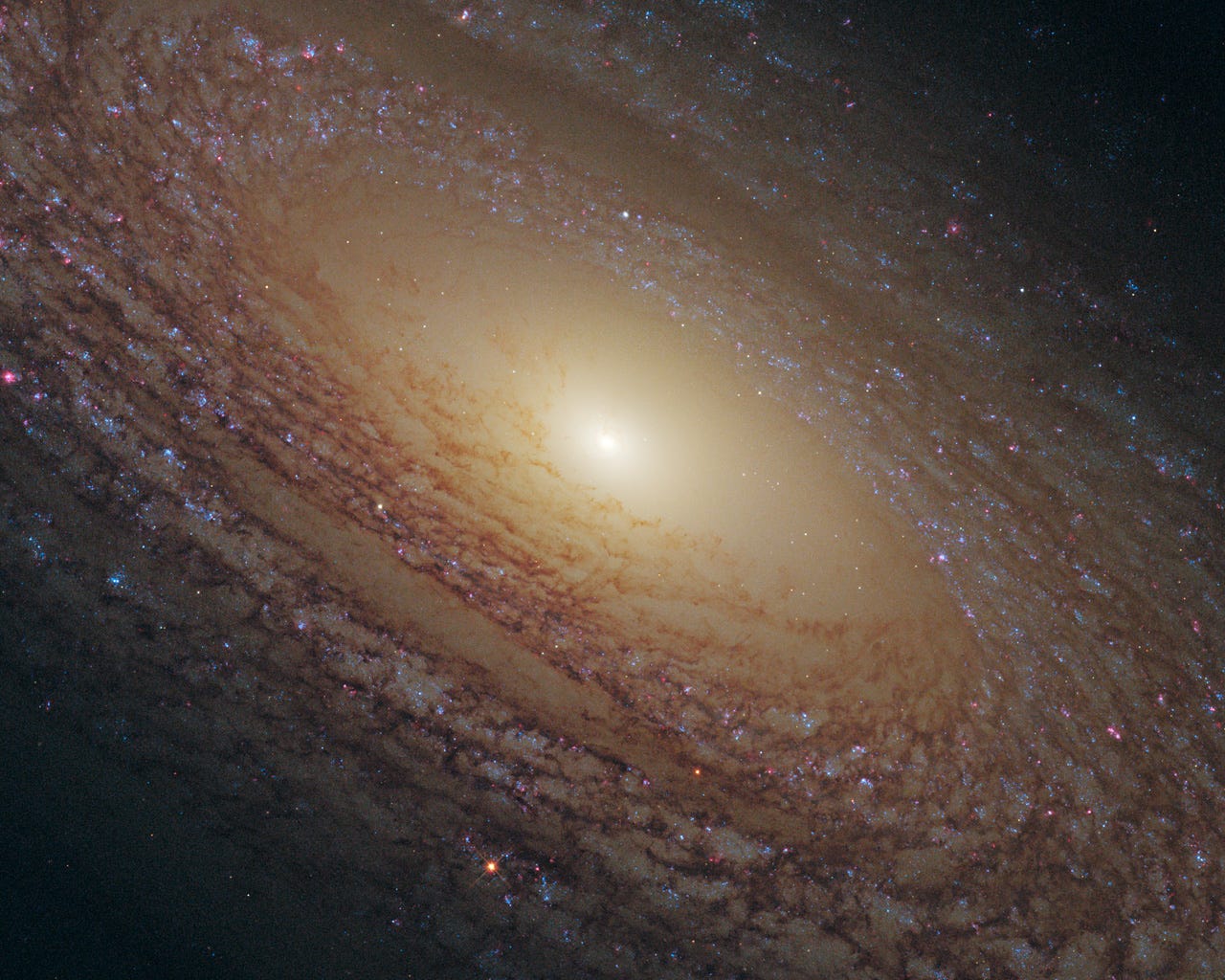

Spiral Galaxy NGC 2841, Hubble Telescope 2011

New York, Joel Meyerowitz 1982

Afterword: Lessons from the Playroom

Perhaps the most charming reminder of what it means to be unembarrassed by our preferences is observing little ones at play:

“Children upset the customary hierarchy of importance. We buy them an expensive toy, and they prefer the box to its contents. They spend an hour examining a brick wall or a zip. They can’t get enough of trying out the light switch.”5

The box, the wall, the zip, the switch - children have no concept of what “should” interest them. They simply follow their inclinations. But as we grow older, this intuition is dulled. We start to filter our choices through the lens of approval and practicality, setting aside what truly delights us in favor of what seems acceptable or impressive.

The playroom holds a timeless invitation: to care about what we care about, without apology. If we can let go of the need to justify our choices - if we can recapture even a fraction of that innocent confidence - we might rediscover the joy of living a life that feels faithful to who we are.

Child Playing with a Toy Truck (after Picasso), Tom Sachs 2023

When Nietzsche Wept, Irvin Yalom

Questions That Have No Right to Go Away, David Whyte

A close friend of mine recently experimented with simplifying his life to focus on meditation. Aware of how this might affect our usual rhythms, he sent me a thoughtful message explaining his intentions. He also shared that, while he wouldn’t be texting or going out much, I was always welcome to join him at the park for moments of quiet fellowship.

Far from seeing his choice as selfish or disruptive, I found it inspiring. I admired his directness, consideration and self-respect, and his example reminded me of an ideal from the early 20th century:

The Charleston Farmhouse was a country retreat for a circle of artists, writers and thinkers known as the Bloomsbury Group. Members - including Virginia Woolf, John Maynard Keynes, E.M. Forster, Bertrand Russell and Roger Fry - gathered here to pursue their individual projects while sharing communal meals rich with lively conversation and creative exchange. It was a space where individuality and connection flourished in harmony.

The Social Contract, Jean-Jacques Rousseau

The Good Enough Parent, The School of Life